Can Poland Throw the EU into Disarray or Is It an Empty Threat?

The government of the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) party is in trouble. Its parliamentary majority is crumbling. Inflation could reach double-digits this year. And its “Polish Deal” package of reforms is proving a flop. Last year, the European Commission rejected Poland’s national recovery plan and withheld its slice of the coronavirus recovery fund worth 24 billion euros in grants due to the collapse of the rule of law in the country.

Facing its most severe political crisis since it won power in 2015, PiS is contemplating how to fight back. Its main target is the EU’s “Fit for 55” climate package designed to enable the EU to achieve its key goal of reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 55 per cent by 2030. Deputy Prime Minister Jacek Sasin recently told the Sejm: “We will do everything we can to prevent the Fit for 55 package from taking effect.”

But Warsaw is flexing its muscles to lash out against the EU more generally. The PiS government has rejected the judgments of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) on its reforms of the judiciary. And Warsaw refuses to pay the penalties imposed by the CJEU, which to date amount to over 130 million euros. The Commission announced that it would collect the amount from the budget funds due to Poland; Warsaw has warned of retaliation.

“This issue will have to be put very clearly and strongly on the forum of the EU institutions, including decisions such as veto on various issues that are important for the EU,” the leader of the PiS parliamentary caucus, Ryszard Terlecki, said in a recent interview.

First shots fired

Some believe that the ‘nuclear war’ against the EU has already begun. As reported by Politico, Poland – together with Hungary and Estonia – is blocking the EU’s efforts to introduce a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15 per cent. Poland’s “no” would deal a big blow to the EU by preventing it from living up to its obligations under the deal reached under the auspices of the OECD in July of 2021.

A desire to give Brussels a punch on the nose probably plays a role, but Poland does have rational arguments to oppose the current plans.

The PiS-led government has actually always supported a global corporation tax, arguing that large companies should pay income tax where they actually make a profit. This is the first pillar of the agreement concluded last year within the OECD. The second pillar of the deal is the introduction of a minimum corporate income tax (CIT) rate of 15 per cent (higher than currently in Poland) in all signatory countries of this agreement.

The problem is that only the second part of it is to enter into force for now: the EU intends to adopt a directive that will result in the mandatory increase of CIT in countries where it is now lower than 15 per cent. Poland and other Central and Eastern European countries would lose out on this. While their tax competitiveness in relation to Western European countries would decrease, important concessions for poorer countries agreed under the first pillar of the agreement could not come into force. For that to happen an international convention needs to be ratified. It will take time. Warsaw’s position is thus not irrational: let’s postpone the entry into force of the directive on the minimum CIT until the entry into force of the convention.

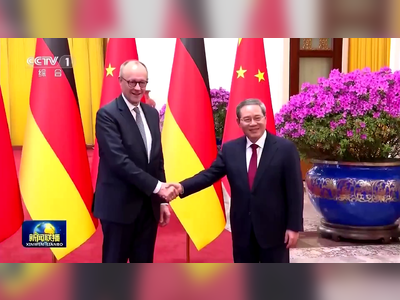

Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki (2-R) attends a closed-door

National Security Council meeting over Russia-Ukraine tensions at the

Presidential Palace in Warsaw, Poland, 28 January 2022.

Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki (2-R) attends a closed-door

National Security Council meeting over Russia-Ukraine tensions at the

Presidential Palace in Warsaw, Poland, 28 January 2022.

Other weapons in the arsenal

What are the other weapons Warsaw is holding in its arsenal? Jacek Saryusz-Wolski, an MEP of PiS, recently presented a list of possible measures claiming that Warsaw has “powerful leverage” to force the EU into concessions. On closer inspection, however, Warsaw’s nuclear options are far less impressive.

A veto against the European Emissions Trading System (ETS) floated by PiS is not possible. ETS is a climate policy instrument where the community method applies and its reform cannot be blocked by a single country. The same is true for the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), which would impose a tax on goods imported into the EU with a high carbon footprint to protect European producers. Besides, for Poland to try to prevent the border carbon tax would be absurd. In March 2021, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki emphasised: “A carbon footprint fee must be introduced at the external borders of the European Union. We are in favour of this solution because it is a good solution for Polish industry”.

The situation is different with PiS’s third secret weapon: the EU energy tax. The current EU directive from 2003 is outdated and does not match the new climate and environmental goals that the EU has set. On taxation unanimity is required. In other words, the PiS government could actually fire a cannon and block the raising of fees as proposed by the Commission.

Would that amount to blowing up the Fit for 55? Hardly. It would certainly result in more pressure to further tighten the policy under the emissions trading system that Poland is complaining about and where there is no veto anymore. Poland has even more to lose. What amount of revenues (Modernisation Fund) and “discounts” granted to the country under the ETS scheme will depend on the Commission and other EU countries. Planting dynamite under the Energy Tax Directive could turn out to be a time bomb that will eventually explode in Poland’s own backyard.

There is yet another possible theatre of war with Brussels: the new Own Resources decision, which will be required in order to use a share of the revenues from the planned new EU taxes – the corporate tax, revenues from the ETS and the carbon border tax, and the previously adopted tax on plastic – to repay the debt the EU has incurred for the 724-billion-euro EU Recovery and Resilience Facility. Poland already tested the nerves of the EU in the spring of 2021 when it threatened to veto the decision required then to activate this huge coronavirus recovery fund.

But this is a paper tiger, too. The vote is not necessary anytime soon. The EU debt only needs to start being repaid from 2028, so Brussels has until the end of the current long-term budget in 2027 to deliberate about the new sources. Yet even if the EU fails to adopt the Own Resources decision, then member states themselves will have to repay their debt anyway, either by increasing their contributions to the EU budget or each paying out of their own pocket. So Poland would have to pay up anyway.

The PiS government might also try to block political conclusions of EU summits and the adoption of such documents as the Strategic Compass. But PiS does not have its finger on any nuclear button; at most it’s a button on a video game console. Poland has legitimate interests in emissions trading, the carbon tax and the corporate tax, and should strive to have them heard. Not every objection and not every harsh word from Poland in Brussels is an attempt at blackmail. But the game that its leaders are considering playing against Brussels is not only harmful for Poland, it’s also doomed to failure.