The enigma of Europe's submerged behemoth

When we think of Italy's volcanoes, we may assume that Etna, which overshadows Sicily, and Vesuvius, which famously destroyed Pompei, present the biggest danger to the peninsula's population and tourists. Yet there is another monster that could wreak havoc to the southern peninsula and its islands.

Its name is Marsili, and it is located around 175km (110 miles) south of Naples. With a height of 3,000m (9,800ft), and a base 70km long by 30km wide (43 by 19 miles), Marsili is a true giant. It is the largest active volcano in the whole of Europe. You won't ever see it, however, since its peak is 500m (1,640ft) under water, in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Scientists have known of Marsili's existence for a century, but it is only within the last decade that they have started to investigate the dangers that Marsili might pose – and their findings are concerning. According to some recent models, its activity could potentially trigger an enormous tsunami, with a 30m-high (98ft) wave hitting Calabrian and Sicilian coasts.

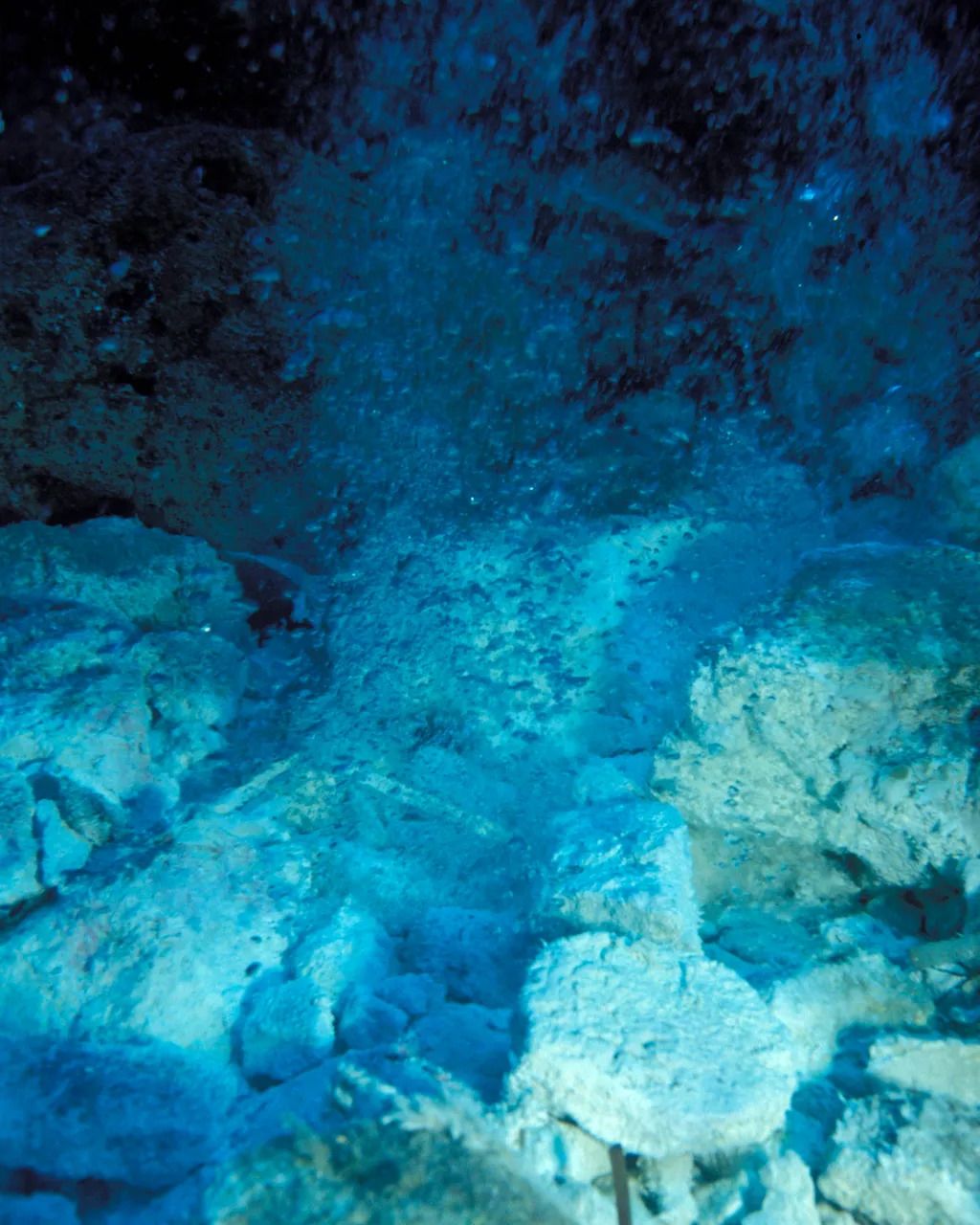

Beneath the waves near the Aeolian islands, volcanic fissures bubble gases that force their way up through the Earth's crust

Beneath the waves near the Aeolian islands, volcanic fissures bubble gases that force their way up through the Earth's crust

Worse still, there would be next-to-no warning that the disaster was imminent – a fact that is leading some scientists to call for new technology to monitor the Mediterranean's movements.

An ancient menace

In terms of sheer size, Marsili cannot compete with Tamu Massif, beneath the north-west Pacific Ocean, which is around 4,460m (14,600ft) tall, and may house a complex of several separate volcanoes. Tamu Massif is extinct, however, whereas Marsili continues to rumble. It lies near the boundary of the Eurasian and African tectonic plates – movement that results in heightened geological activity.

In the worst-case scenario, a 20m-high (66ft) wave could crash into Sicily and Calabria within 20 minutes of a landslide

It is just one of many volcanos in an arc off the south coast of Sicily and the east coast of southern Italy. Some of these have formed land masses, the Aeolian islands – Stromboli, Lipari, Salina, Filicudi, Alicudi, Panarea and Vulcano, which was named after the Roman god of fire and which gave us the general name for all such fissures in the Earth's crust. And for every one of these visible islands, 10 volcanoes lurk below the sea.

According to Guido Ventura, a volcanologist at Italy's National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, Marsili was born around a million years ago. Over the millennia, it came to amass 80 eruptive cones, spanning from the north-north-east to the south-south-west, alongside many fissures and fractures that could each vent lava.

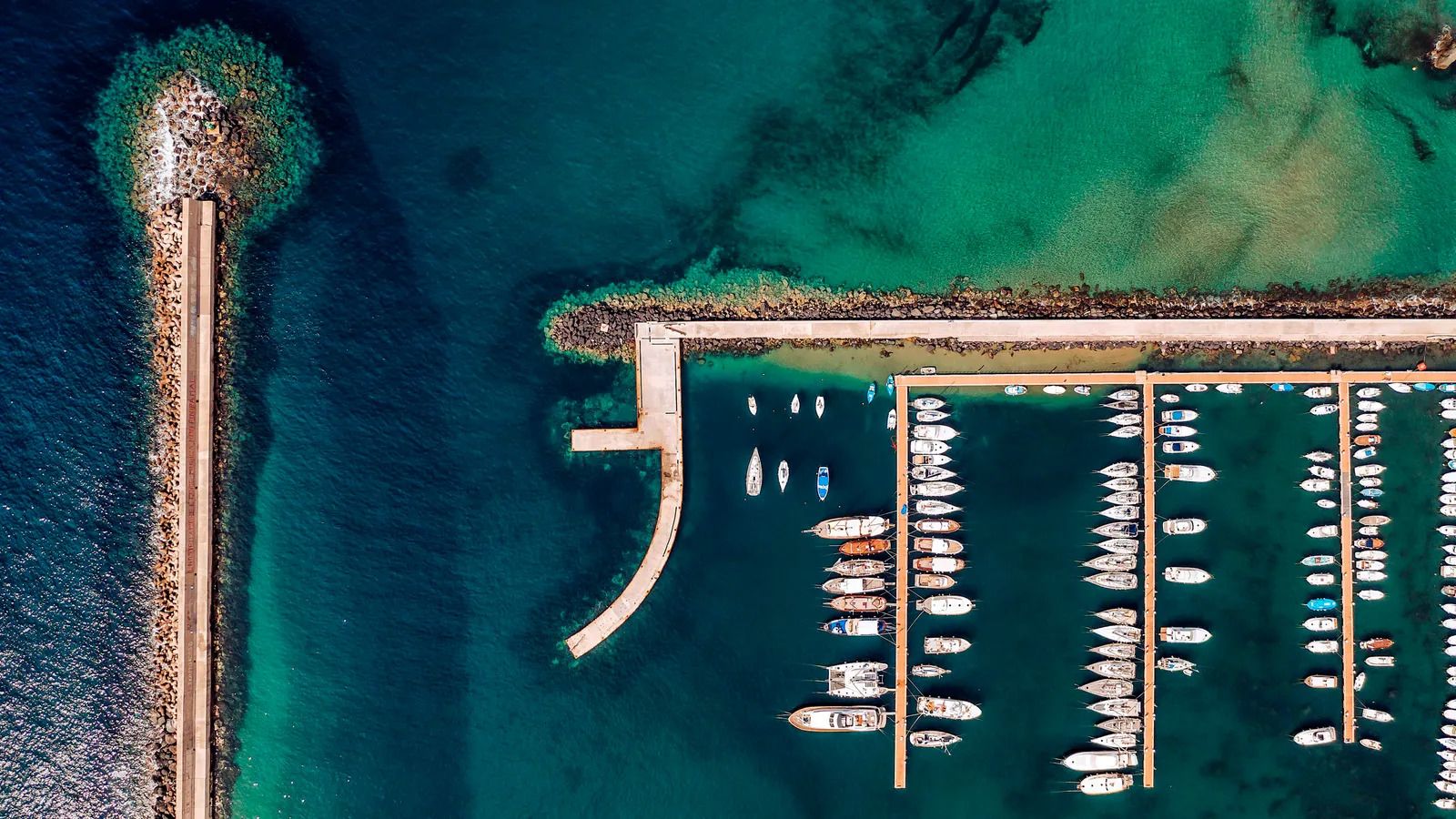

The Aeolian islands are formed from a string of volcanoes in the Tyrrhenian Sea to the north of Sicily

The Aeolian islands are formed from a string of volcanoes in the Tyrrhenian Sea to the north of Sicily

Thanks to its depth beneath the sea, this potential time-bomb lurking on south Italy's ocean floor was only discovered 100 years ago. "It was only in the early 20th Century that people started to map the sea basins," says Ventura. This was driven, in part, by the military's increasing use of submarines, and the world's new international communication systems, which required telegraph cables to be draped along the seabed. As a result of these efforts, cartographers finally identified the seamount in the 1920s. They named it after the polymath Luigi Ferdinando Marsili (1658-1730), who, among many other achievements, wrote the first treatise on hydrography.

If knowledge of the existence of Marsili was a long time coming, the emergence of scientific research into its activity is even more recent – with detailed studies only appearing in the 2000s. According to these findings, the volcano's last eruption occurred a few thousand years ago. Today, its activity is limited to gentle rumblings, with gaseous emissions and low-energy tremors, Ventura says.

This does not, of course, preclude a more dramatic return to life in the future; Marsili may simply be dozing. If it were to erupt again, the lava and ashes produced by the explosion would be absorbed by the 500m (1,640ft) of water above the seamount; there's little risk that the fiery belch could ever reach the land or harm local populations.

Vulcano was named after the Roman god of fire, which has been adopted to become the generic name for all volcanoes

Vulcano was named after the Roman god of fire, which has been adopted to become the generic name for all volcanoes

"The danger isn't the eruption, but the possible underwater landslides," says Ventura. If the seismic movements beforehand, or the explosion itself, led one of its flanks to collapse, it would displace such a large volume of water that it would trigger a tsunami.

The devastation of Naples

We now know that submarine landslides from the Aeolian arc of volcanoes could have contributed to past tragedies.

In 1343, for instance, the poet Petrarch described a terrible sea storm that devastated the Bay of Naples, leading to hundreds of deaths.

A recent study by Sara Levi at the State University of New York and colleagues suggests this may have been the result of a tsunami, originating on Stromboli. Analysing archaeological evidence from the volcano, the team found evidence of an ancient landslip, resulting in a tsunami that reached the Calabrian coast.

A more recent eruption at Stromboli, in 2002, led to two tsunamis in 2002. The waves only affected the island itself, however, without reaching the mainland – and no one was killed by the surge.

A landslide on the slopes of Marsili could cause a 20m-high (66ft) wave travelling towards the coast of the Bay of Naples

A landslide on the slopes of Marsili could cause a 20m-high (66ft) wave travelling towards the coast of the Bay of Naples

Unfortunately, we can't yet calculate the precise threat from Marsili. "We just don't have enough data," says Glauco Gallotti, a physicist at the University of Bologna. But there are good reasons to think it may pose a danger, he says. For one thing, the continuing hydrothermal activity could have weakened the volcano's rocks. What's more, recordings of microearthquakes shows that lava is still churning in the magma chamber, he says. For both these reasons, we should take the possibility seriously with further research.

In a paper published earlier this year, Gallotti's team considered five different scenarios, each examining the effects of different possible landslides. In the first couple of cases, the displacement of water was minimal – leading to a wave of just a few centimetres in height.

A collapse on the north-western flank, however, proved to be more serious – leading to a 3-4m high (10-13ft) wave reaching southern Campania, and a 2-3m high (6.6-10ft) wave hitting Calabria and Sicily within 30 minutes of the event. This is worth taking seriously, since a "scar" on Marsili's seamount suggests that a similar landslide may have occurred in the past. "And it could have generated waves between 1m and 3m high [3-10ft]," says Gallotti.

The worst-case scenario involved the collapse of the southern-central summit and the eastern flank. According to Gallotti's calculations, it would result in a 20m-high (66ft) wave reaching Sicily and Calabria within 20 minutes. Further research will be needed to assess the probability that this will occur, he emphasises. "But we can't [yet] rule out the possibility."

If an eruption does happen, the human cost may depend on the time of year, and whether or not the tsunami arrived in the peak of the tourist season. "The south of Italy is vastly populated in the summer," Gallotti says. The elevation of Italy's coastline means that people should be safe if they were around one kilometre inland, he estimates.

Seismic sisters

Ventura agrees that these risks should be explored. "It's clear that Marsili needs to be monitored for possible instabilities on its flanks."

As the events at Stromboli had shown, Marsili may be the biggest volcano in Europe, but its sisters could also pose significant threats. "It's worth remembering that in the Tyrrhenian Sea, as in the Strait of Sicily, there are at least 70 underwater volcanoes, whose story, in some cases, is totally unknown," says Ventura.

The damage caused by a tsunami caused by a collapse of Marsili would depend on whether it coincided with peak tourist season

The damage caused by a tsunami caused by a collapse of Marsili would depend on whether it coincided with peak tourist season

Of particular concern is the Palinuro volcano, located 65km (40 miles) off the coast of Cliento. According to Gallotti, recent studies show that the volcanic complex has a 150m-layer (490ft) of loose material that could be displaced with seismic movements. Ideally, future surveys will provide further details of that structure and its chances of collapse.

If the risk is significant, the Italian government may need to take action to pre-empt the potential disaster. At the moment, there is no good monitoring system to warn Italian people of an impending tsunami. But it need not be too difficult to build, Gallotti says. He points out that a network of buoys, fitted with motion sensors, should be able to detect characteristic differences in the sea's movements that signal the emergence of a tsunami. This could send an automatic SMS alert to people in the areas affected – allowing them to reach higher ground before the tsunami hit.

Ventura suggests it may also be possible to monitor the movements of the volcano itself. "In the last 40 years the technology for monitoring active volcanoes has made huge strides," he says.

In addition to an early warning system, Gallotti would also like to see greater awareness of the potential danger – among the public and policy makers. As evidence, he cites a paper by Teresita Gravina, at Guglielmo Marconi University, Nicola Mari at the University of Glasgow, and colleagues, which recently assessed people's risk perception in southern Italy.

In general, people were aware that tsunamis could occur in the area, but their knowledge was hazy. When asked about the most recent events, for example, only 3.3% of the people who answered mentioned the 2002 tsunami at Stromboli, for instance. Most believed themselves to be ill-informed about the events, with limited knowledge of the tsunami's potential causes or the best ways to act, were another to occur.

"This is quite serious," Gravina and Mari told BBC Future in an email. "It's probably due to the fact that in Italy there's little communication on these subjects. To know how a seismic phenomenon, or a tsunami, forms is very important, because you can assess completely different scenarios and the different behaviours that would be necessary to avoid the danger." Any attempts to design an effective early warning system would need to consider the behaviours of the different communities, they say. (We've already seen this with Covid-19 – two populations can react to exactly same information in very different ways.)

There have been some positive steps. A recent project in Salerno, organised by Italy's Civil Protection Department, attempted to simulate the emergency caused by a tsunami. "This could have increased their awareness of the risk," Gravina and Mari say. But for most people, the danger of an underwater landslide, caused by a submarine volcano, is still little understood – meaning that much more work is needed to educate people of the possibility.

The danger of a tsunami may seem remote – but should it come to pass, a little knowledge could help save thousands of lives.