The 100-year-old fiction that predicted today

One day in 1920, the Czech writer Karel Čapek sought the advice of his older brother Josef, a painter. Karel was writing a play about artificial workers but he was struggling for a name. "I'd call them laborators, but it seems to me somewhat stilted," he told Josef, who was hard at work on a canvas. "Call them robots then," replied Josef, a paintbrush in his mouth. At the same time in Petrograd (formerly St Petersburg), a Russian writer named Yevgeny Zamyatin was writing a novel whose hi-tech future dictatorship would eventually prove as influential as Čapek's robots.

Both works are celebrating a joint centenary, albeit a slippery one. Čapek (pronounced Chap-ek) published his play, RUR, in 1920 but it wasn't performed for the first time until January 2021. And although Zamyatin submitted the manuscript of his novel, We, in 1921, it was mostly written earlier and published later. Nonetheless, 1921 has become their shared birth date and thus the year that gave us both the robot and the mechanised dystopia – two concepts of which, it seems, we will never tire. As Čapek wrote in 1920, "Some of the future can always be read in the palms of the present".

The plan goes awry – humans grow lazy and infertile while the robots plot genocidal revolution

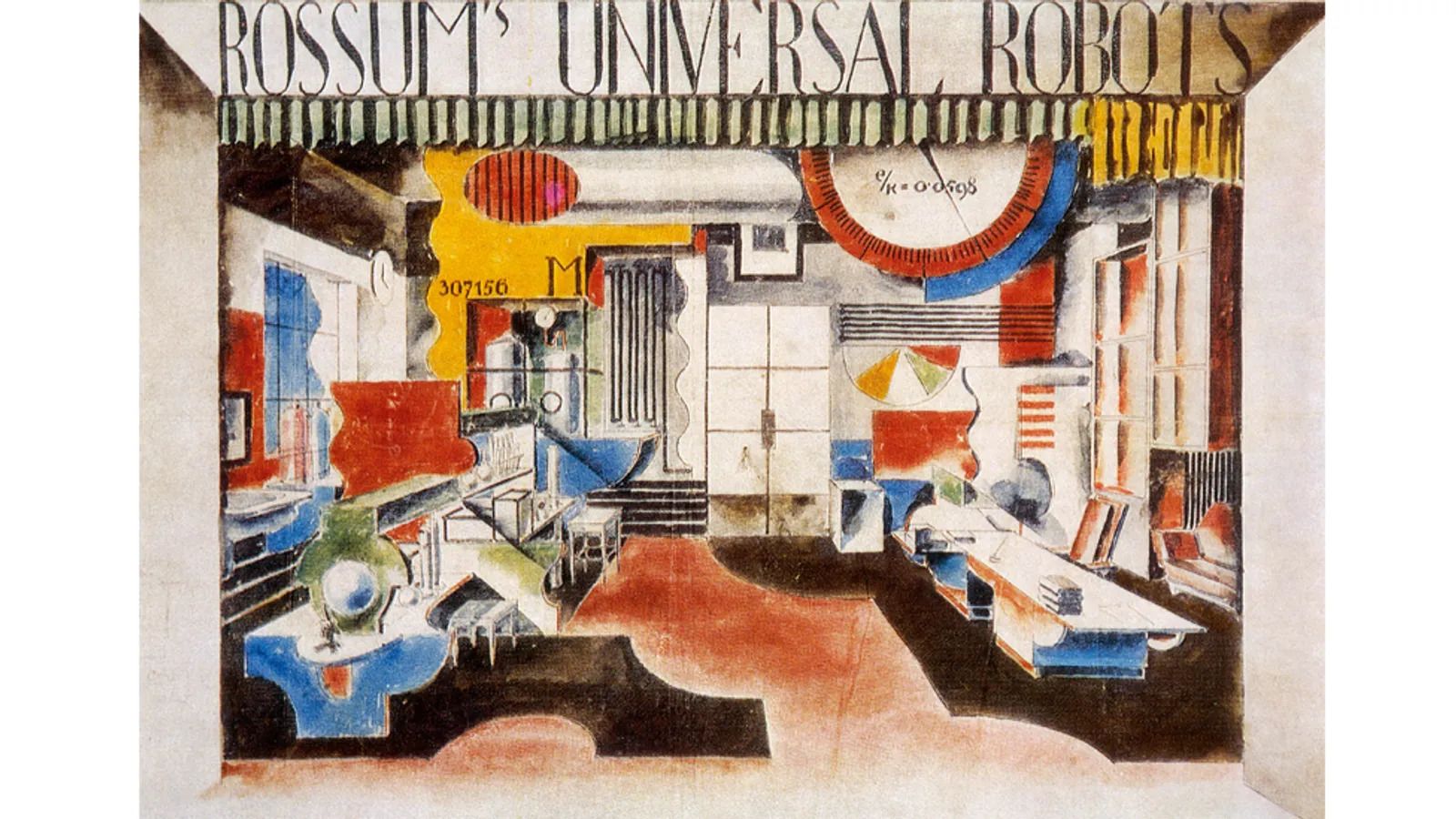

RUR stands for Rossum's Universal Robots, Rossum being a pun on the Czech word rozum, or "reason", and Robota meaning "serfdom". Čapek's "comedy, partly of science, partly of truth" is a Frankenstein story for the age of mass production. Rossum's robots are more akin to the replicants in Bladerunner than to C-3PO or WALL-E: bioengineered artificial humans, almost indistinguishable from the real thing, who do most of the world's labour so that their masters can enjoy a post-work utopia. Inevitably, the plan goes awry. Humans grow lazy and infertile while the robots plot genocidal revolution. "We have made machines, not people, the measure of the human order," Čapek later wrote, "but this is not the machines' fault, it is ours."

RUR was an immediate international success; by 1923 it had been translated into 30 languages, and staged in the West End and on Broadway. Remarkably, it became both the first radio play aired by the BBC, in 1927, and the world's first televised science-fiction drama, in 1938. Fond allusions to RUR have since appeared in Star Trek, Doctor Who and Futurama.

The 1920 play RUR (Rossum Universal Robot) by Karel Čapek was a big hit – and proved to be very influential

The 1920 play RUR (Rossum Universal Robot) by Karel Čapek was a big hit – and proved to be very influential

We is an equally important piece of work. A number of writers, including Jack London and HG Wells, had previously attempted anti-utopian novels but Zamyatin was the first to combine a coherent concept with a satisfying narrative to create something like a blueprint for dystopia. We takes place in the ultra-rational One State, where everything from work to sex to music is mathematically regimented, uniformed "ciphers" have numbers rather than names, and everybody is surveilled by the Guardians, under the command of an enigmatic dictator known as the Benefactor. The protagonist, D-530, is a drab and dutiful rocketship engineer who is seduced into an underground revolutionary movement by a charismatic female dissident called I-330. After a great deal of mayhem, the rebels are routed, I-330 executed and D-530 lobotomised into total obedience. Zamyatin insisted on the freedom to be imperfect, irrational and sometimes unhappy, which is to say human.

If you have had any experience with science fiction, you will probably have imbibed some trace elements of RUR and We

If that plot sounds a little like 1984, then that's because George Orwell admired We so much that he attempted to get a proper English translation published in the 1940s, and is largely responsible for its modern reputation. Although he wrote the outline for his novel before he knew that We existed, it clearly influenced him on the level of narrative and character. Its influence is also obvious in Ayn Rand's Anthem, George Lucas's THX 1138, Kurt Vonnegut's Player Piano and (to more cheerful effect) The Lego Movie.

The two books' combined legacy is incalculable – if you have had any experience with science fiction, you will probably have imbibed some trace elements of RUR and We. Far less well-known, however, are the parallel lives of the men who created them. Čapek and Zamyatin were born six years apart, and died within two years of each other, shortly before World War Two. Both were free thinkers of extraordinary intelligence and courage who wrote plays, novels, stories, translations and journalism. Both were anglophiles with a particular affection for HG Wells. Both were extraordinarily alert to the dangers of dogma, tribalism and the corruption of language in the inter-war years.

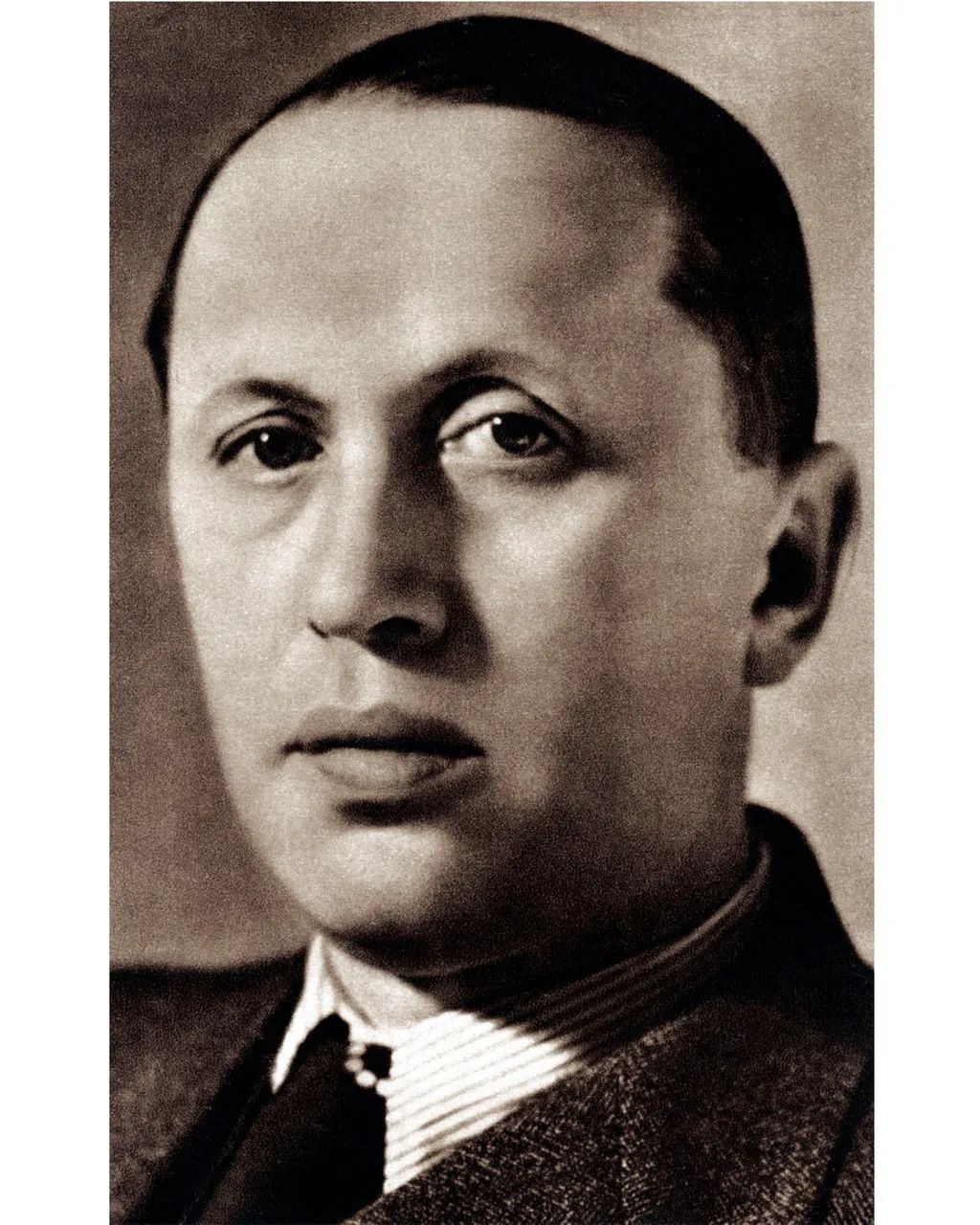

Czech writer Karel Čapek introduced and made popular the word "robot" in his plays

Czech writer Karel Čapek introduced and made popular the word "robot" in his plays

Quick to identify the threat of totalitarianism, they were both ultimately crushed by it. Both their lives were changed by their most famous works but in radically divergent ways: RUR made Čapek a literary superstar, while We made Zamyatin a pariah. You can't really understand their vast gifts to the popular imagination without knowing a little about their lives and why they were driven to write fables about the horrors that technology can unleash when it converges with the worst of human nature.

Yevgeny Ivanovich Zamyatin was born in 1884 in the Russian town of Lebedyan, 400km (249 miles) south of Moscow. His father was an Orthodox priest and his mother a musician. Zamyatin graduated from school in 1902 with a gold medal for flawless grades and went to study naval engineering at the St Petersburg Polytechnic Institute, where he became a Bolshevik. He was a questing, combative soul who invariably chose the hardest path. "I've always sought novelty, variety, dangers – otherwise [life] would all have seemed too cold, too empty," he told his future wife Lyudmila Nikolaevna in 1906.

Karel Čapek was born in 1890 in a village in northern Bohemia, which then belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A childhood bout of scarlet fever left him with Bechterew's disease, a form of arthritis which gave him chronic spinal pain, headaches and a stooped posture. He walked with a cane and was unable to turn his head. His brain, however, was formidable. In a 1932 radio talk called How I Have Come to Be What I Am, he wrote that he had inherited his pragmatism and intellectual curiosity from his father, a country doctor, and his "romantic sensibility" and "fantasticality" from his mother. Despite being expelled from high school in 1905 for belonging to a clandestine pro-independence society, he went on to study literature in Berlin and Paris.

Around the same time that Čapek was being expelled, Zamyatin was being arrested for the first time by the Tsar's secret police for belonging to a Bolshevik cell. He was held in solitary confinement for three months, an experience that inspired his first short story, Alone. When he was arrested again in 1911, and exiled from the city, he began writing novels. "If I mean anything in Russian literature, I owe it all to the Petersburg Secret Police," he quipped in an autobiographical sketch, neglecting to mention that this was also when he began suffering from depression and chronic colitis.

When World War One broke out, Čapek was exempted from military service on account of his condition and continued his studies, graduating from the University of Prague with a doctorate of philosophy in 1915. Zamyatin, however, had valuable engineering skills, so the Russian government dispatched him to Newcastle in 1916, where he designed icebreakers for the Russian navy. Like D-530, he was a shipbuilder. Zamyatin's gentlemanly bearing, dry wit and emotional reserve led friends to nickname him "the Englishman". He returned to St Petersburg just in time for the revolution.

Fictional revolutions

The events of October 1917 loom over both We and RUR. The fictional revolutions may be opposites – Čapek's robots overthrow their human masters while Zamyatin's rebels are crushed by the technological state – but in both cases the machines win. Zamyatin was warning of Russia's potential to replace one tyranny with another but, like Čapek, he was also satirising capitalist innovations that made people "machinelike," chiefly the management science of Frederick Winslow Taylor and the assembly lines of Henry Ford. As he explained in a 1932 interview: "This novel is a warning against the two-fold danger which threatens humanity: the hypertrophic power of the machines and the hypertrophic power of the State." The third context was the aftermath of the first mechanised global conflict, whose casualties included pre-war optimism about technological progress. A war fought with tanks, aeroplanes and poison gas, Zamyatin wrote, reduced man to "a number, a cipher".

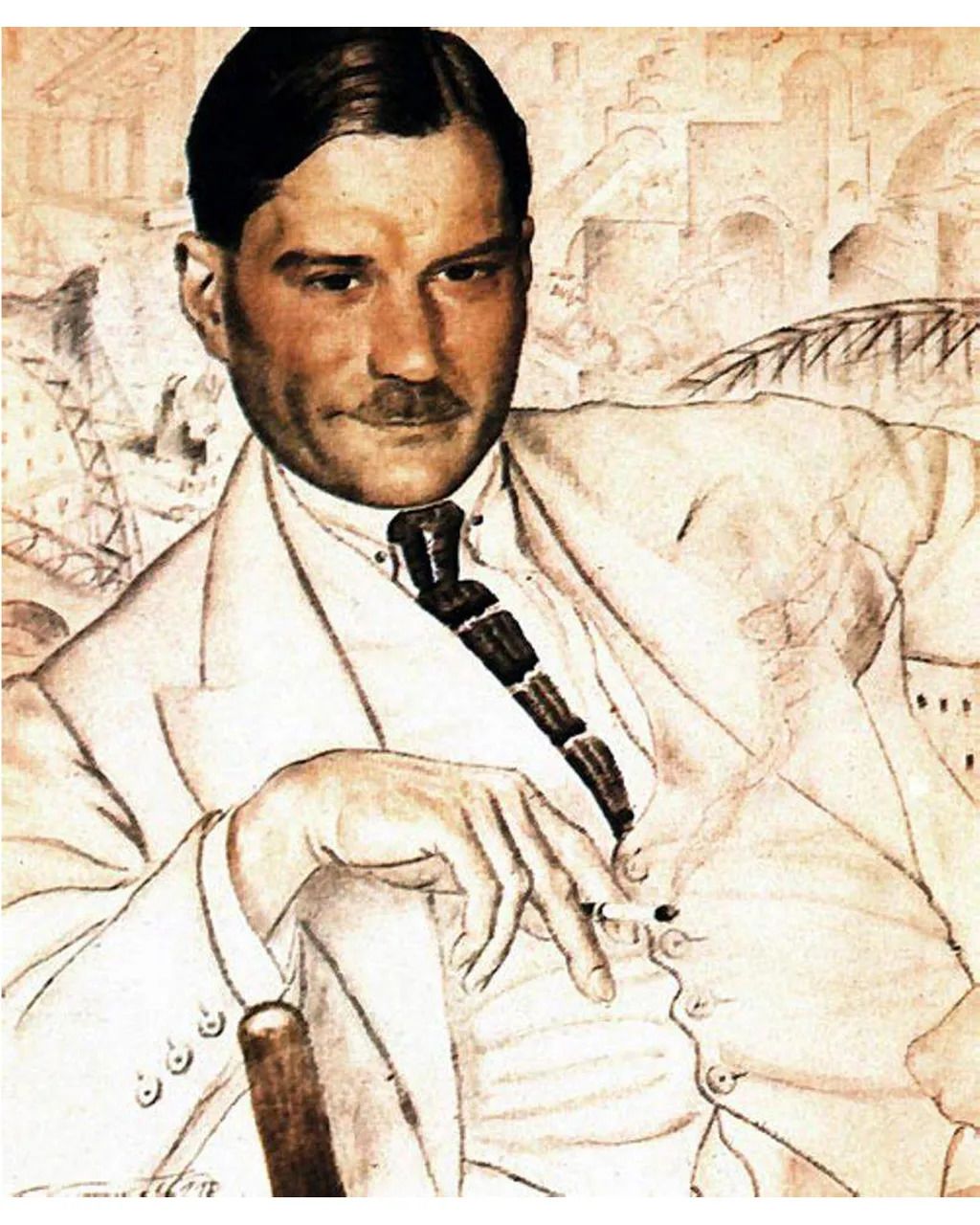

A 1923 portrait of the author Yevgeny Zamyatin by Boris Koustodiev

A 1923 portrait of the author Yevgeny Zamyatin by Boris Koustodiev

With the defeat of Austro-Hungary, Czechoslovakia became an independent nation in October 1918. "It was a revolution in which not even a drop of blood was spilled, in which not even a window was broken," Čapek would write proudly on its 20th anniversary. He became his young country's first literary celebrity. During 1920 and 1921 alone, as well as writing RUR, he started a column for the progressive People's Newspaper, became a writer-director at Prague's Vinohrady Theatre, and launched a weekly intellectual salon in his garden whose attendees became known as the "Friday Men". He also fell in love with a 17-year-old actress named Olga Scheinpflugová, who he eventually married in 1935. His letters to Olga revealed a shy, insecure side (he once attended a performance of RUR with the French writer Romain Rolland and spent the whole show apologising for its flaws) but on the page he radiated confidence and wit. Zamyatin likewise concealed his vulnerabilities beneath a glossy shell of charm and professionalism.

While Čapek was revelling in his country's new dawn of freedom and democracy, Zamyatin was writing as early as 1918 that the revolution "has not escaped the general rule on becoming victorious: it has turned philistine… And what every philistine hates most of all is the rebel who dares to think differently from him". Blending politics, philosophy and physics, he warned in a string of brilliant essays that revolutionary energy was freezing into something static and oppressive, and argued that the only cure was permanent revolution. "Revolutions are infinite," I-330 tells D-530 in We. Zamyatin's heretical philosophy inevitably made him unpopular with the new regime. He was denounced as "an internal emigré" by Trotsky himself and twice arrested by the secret police – in 1919 and 1922. "It's amusing, isnt it?" he wrote to the critic Alexsandr Voronsky. "That I was imprisoned then as a Bolshevik, and now I'm imprisoned by the Bolsheviks."

Early science fiction was an inherently political playground for ideas about how the world was, or could be

He would have had an even harder time without the protection of Maxim Gorky, the literary giant who carved out a liminal space for those vulnerable writers who supported the revolution but were not loyal communists. Hard-working and well-liked, Zamyatin joined Gorky's publishing house World Literature and personally oversaw the publication of translations of books by HG Wells, whom he met in Petrograd in 1920. Čapek also met Wells, on a visit to England in 1924, and his "remarkable philosophic-fantastic novel" The Absolute at Large (1922) was praised by Zamyatin as an example of the influence of Wells's "mechanical, chemical fairy tales". Thanks to the author of The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds, early science fiction was an inherently political playground for ideas about how the world was, or could be.

The 1920 dystopian novel We by Yevgeny Zamyatin explored human nature, technology and politics

The 1920 dystopian novel We by Yevgeny Zamyatin explored human nature, technology and politics

While Zamyatin dazzled and goaded his readers with radical ideas and angular, ultra-modern prose, Čapek sought to befriend his. Claiming "I am interested in everything that exists," he wrote more than 3,000 articles, as well as novels, stories, plays, screenplays and children's books. His short columns, or feuilletons, read like precursors of Orwell in their chatty, companionable tone; their witty aphorisms; their celebration of ordinary lives and the natural world; their criticism of snobbery and elitism; their hatred of dehumanising abstractions; and their fascination with language. A dozen years before Orwell's landmark essay Politics and the English Language, Čapek was describing the relationship between bad writing and dangerous politics: "The cliché blurs the difference between truth and untruth. If it were not for clichés, there wouldn't be demagogues and public lies, and it wouldn't be so easy to play politics, starting with rhetoric and ending with genocide." He was, however, capable of greater kindness and optimism about human nature than Orwell. "I believe that seeing is great wisdom," he wrote in 1920, "and that it's more beneficial to see a lot than to judge".

Čapek was a close friend of Tomáš Masaryk, Czechoslovakia's first president, whose government he saw as a humane, democratic middle way between the rising extremes of communism and fascism. In 1924, he wrote an essay called Why Am I Not a Communist? His answer was that communists weren't really interested in people as individuals, only as revolutionary masses. "Hatred, lack of knowledge, fundamental distrust, these are the psychic world of communism," he wrote. By contrast, "I count myself among the idiots who like man because he is human". He believed that people should be "revolutionary like atoms", and change the world by first changing themselves.

The essay infuriated Czech communists but they were not in charge. For Zamyatin, living in a one-party state, such a declaration of political independence was perilous. As Stalin succeeded Lenin, his letters were censored, his articles were rejected and the periodicals and publishers he worked for were shut down. In 1925, he was informed that We was, as he suspected, officially unpublishable in Russia. "I often encounter difficulties, because I'm an unbending and self-willed man," he told a friend. "And that’s how I shall remain".

In 1929, his enemies used the unlicensed publication of Russian-language extracts from We by Russian emigrés in Prague as an excuse to condemn Zamyatin for disseminating "anti-Soviet" ideas, and thus to pass what he called a literary "death sentence". In 1931, he won permission from Stalin to leave Russia forever but his life in exile in Paris with Lyudmila failed to revive him as a writer. After a few frustrating years consumed by an unfinished novel and mostly unproduced screenplays, he died of heart failure on 10 March, 1937.

Čapek, conversely, went from strength to strength. He was nominated more than once for the Nobel Prize for Literature, and asked by Wells to become the president of the international writers' group PEN. Yet his success was clouded by his awareness of Hitler's designs on his homeland, and he became one of Czechoslovakia's most prominent anti-fascists. "All of us have begun to feel that there is something odd and insoluble about the conflicts between world-views, generations, political principles, and whatever else divides us," he wrote in 1934.

Čapek revisited RUR's themes of hubris, greed and conflict in War with the Newts (1936), a spectacularly inventive satire on nationalism, colonialism, militarism and racism. When humans discover a race of intelligent newts living in the sea, they put them to work as slaves, but the fast-evolving amphibians become too numerous to control and demand more living space. Under the Hitleresque command of Chief Salamander, the newts flood and annex vast swathes of land. Čapek explains in War with the Newts how the world will end: "No cosmic catastrophe, nothing but state, official, economic and other causes… we are all responsible for it". There is a similar anti-fascist message in his 1937 play The White Plague, in which a pro-war mob destroys the only antidote to a pandemic, resulting in a kind of national suicide.

In War with the Newts, the European powers sell out China to the newts in the hope of saving themselves. In October 1938, the Munich Agreement between Britain, France and Germany did much the same to Čapek's country. "My world has died," he told his friend Ferdinand Peroutka. "I no longer have any reason to write". Despite denunciations and death threats from the right, he refused to abandon the country he loved. The Gestapo placed him on its hitlist of people to arrest after the invasion of Czechoslovakia.

A laboratory scene from RUR being performed around 1923 in a Berlin theatre

A laboratory scene from RUR being performed around 1923 in a Berlin theatre

Yet when the Nazis arrived at his door in March 1939, they found that they were too late. While working in his beloved garden, Čapek had caught a cold which developed into double pneumonia and he died on Christmas Day, 1938. "As a doctor I know that he died because in those days there was no antibiotics and sulpha drugs," said his friend Dr Karel Steinbach, "but those who say that Munich killed him also have a great deal of the truth". It's unlikely that he would have survived Nazi occupation. Among the Friday Men who died in concentration camps was Josef, who perished in Bergen-Belsen just days before it was liberated. An inscription on Karel's Prague tombstone reads: "Here would have been buried Josef Čapek, painter and poet. Grave far away."

Čapek's writing career coincided almost precisely with the birth and death of independent Czechoslovakia; Zamyatin's extended from the last days of the Romanovs to Stalin's Great Terror. As members of that brave and tragic inter-war tribe of intellectuals who rejected fascism, communism and imperialism alike, they witnessed the crushing defeat of the values that they lived by. Ultimately, the only thing that exceeded their imaginations was their moral courage. Their lives were not blighted by robots or spaceships but by people who had surrendered something of their humanity to unforgiving ideologies. As one of Čapek's characters says in The Absolute at Large, "You know, the bigger the things a man believes in, the more fiercely he despises those who don't. And yet the greatest of all beliefs would be to believe in people".