EU rings alarm bell on China — but isn’t sure how to respond

It’s not the kind of talks China wants Brussels to have — let alone on the cusp of President Xi Jinping prolonging his reign.

Just a day before the Communist Party congress concludes on Saturday and essentially dubs Xi the Chinese leader for life, EU leaders officially began a collective rethink about the bloc’s increasingly fraught relationship with China, displaying a sense of urgency unseen prior to the Russian war against Ukraine.

In a three-hour-long conversation, the 27 EU leaders one by one took the floor at the European Council meeting in Brussels to express their heightened concern.

But while the diagnosis was unanimous — Beijing has grown increasingly bellicose on both the military and economic fronts while cozying up to a warmongering Russia — the recommended treatments were disparate.

Some equated the situation to the EU’s misread of its relationship with Russia. Others shied away from the direct parallel but nevertheless called for the EU to reduce its dependency on China’s technology and raw materials. Then there were those — notably including German Chancellor Olaf Scholz — who insisted the EU must remain a beacon of global trade, even with China.

The varying opinions reflect the difficulties the EU will face in the years ahead as China shifts from looming threat to imminent menace.

“We must not repeat the fact that we have been indifferent, indulgent, superficial in our relations with Russia,” Italy’s outgoing Prime Minister Mario Draghi implored in a closing press conference, relaying the message that many leaders offered during the discussion.

“Those that look like business ties,” he added, “are part of an overall direction of the Chinese system, so they must be treated as such.”

Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo echoed Draghi’s sense of alarm.

“In the past, I think we’ve been a bit too complacent as European countries,” he told reporters. “On some domains, [China is] a competitor — it’s a fierce competitor. On some domains, we also see that they have hostile behavior. … We should understand that in a lot of economic domains, it’s also geostrategic.”

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen went further and gave Xi a personal thumbs down.

“We’re witnessing quite an acceleration of trends and tensions,” she said. “We’ve seen that President Xi is continuing to reassert the very assertive and self-reliant course China has taken.”

Even the generally pro-Beijing Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán agreed the EU should become more “autonomous” during the discussion, according to another EU diplomat.

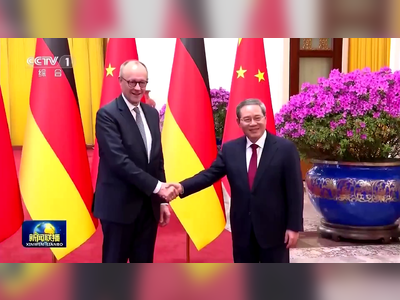

And German Chancellor Olaf Scholz — who is planning a trip to China next month and is set to become the first Western leader to greet Xi as the newly reappointed leader — also warned his fellow EU leaders of Beijing’s economic future, according to a senior diplomat briefed of the no-phone-allowed conversation.

Scholz told fellow leaders that China could well be the source of the world's next financial crisis, while the country is in danger of entering what economists call a middle-income trap, according to the diplomat.

Yet while everyone was eager to spin a line about their China concerns, they split on how to address those fears.

The Baltic countries, whose years of warnings about Russia’s revanchist intentions fell on deaf ears in much of Europe, are pushing a more hard-line approach to China.

“The more Russia threats they face, the less interested they are in working with China,” one diplomat said, referring to the Baltic countries.

Lithuania, for instance, became a target of China’s trade embargo after it began building closer economic ties with Taiwan. Earlier this year, Estonia and Latvia followed Lithuania’s move to leave Beijing’s 17+1 economic club, which they criticize as a Chinese attempt to divide EU countries.

Conversely, Scholz continued to defend Germany’s need to trade with China despite the geopolitical shifts at play. Borrowing some Trump-era rhetoric, he flatly rejected the notion of “decoupling.”

“The EU prides itself on being a union interested in global trade and it does not side with those who promote deglobalization,” he said.

Just this week, Scholz reportedly backed a deal by Chinese state-run shipping giant Cosco to acquire a share of the Hamburg port — despite strong opposition from within his own government.

Asked about the port deal in a press conference, Scholz would only say that "nothing has been decided yet,” adding that “many questions” remained to be clarified.

Possible frustration over Scholz’s trip to China — on which he also plans to bring a business delegation — was also reflected in the EU leaders’ meeting, albeit implicitly. Latvia’s Prime Minister Krišjānis Kariņš, for instance, said China is “best dealt with when we are 27, not when we are … one on one.”

Additionally, as has always been the case, EU countries are at odds over how closely to align with the more anti-China U.S. stance, especially after President Joe Biden’s administration characterized China as his country’s “most consequential geopolitical challenge.”

Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, while backing calls to work with the U.S. on tech development, warned about Europe’s Americanization in handling China relations: “It’s important that Europe operates as self-confident as possible, but also independently, and that there is equality and reciprocity, so that we are not a kind of extension of America but that we have our own politics vis-à-vis China.”

Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin, meanwhile, called on the EU to work with all democracies against China’s rise in the tech field.

“We shouldn't be building that kind of strategic, critical dependencies on authoritarian countries,” she said when asked about the EU's concerns about China. “We would need in the future [to] work with other democratic countries also to build this kind of export routes together, with [the] United States, with Great Britain, with Japan, with South Korea, Australia, India, New Zealand, for example.”