As Kilicdaroglu takes on Erdogan - here's why Turkey's election may well be the most important in the world this year

After two decades in which he has exerted ever greater control over his nation, Turkey's leader finds himself looking at something remarkable - the prospect of losing power.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan has held the job of president since 2014, representing the AK Party (AKP) that he himself founded back in 2001.

Before becoming Turkey's president, he was the country's prime minister, a job that was abolished, with his persuasive backing, six years ago.

Ever since, his grip over Turkey has got ever tighter.

That has meant a variety of things - less media freedom, a fractious relationship with most European countries, not least because of Erdogan's enduring ties with Vladimir Putin, and restrictions on political opponents (many of whom are now in prison).

But above all, Erdogan's rule has recently meant economic turbulence. Inflation in Turkey is now officially somewhere around 40% and, in reality, probably nearer 100%. Nobody really knows, such is the challenge in gauging the world's 11th biggest economy.

He has, variously, made his son-in-law the finance minister, sacked a succession of governors of the central bank, which has been marginalised anyway, and then come to the conclusion that the best way to tackle rising inflation is to lower interest rates - the exact opposite of every other major financial institution in the world.

That's why inflation is soaring, and it's also why Erdogan has dramatically raised both the state pension and the minimum wage.

Earlier this week, with the election looming, he decided to raise the wages of hundreds of thousands of public workers by 45% - good news for them, but hardly the best way to control rampant inflation.

Erdogan's rule has recently meant more economic turbulence

Erdogan's rule has recently meant more economic turbulence

For some across Turkey, none of this matters as much as Erdogan's reputation for toughness.

His supporters, especially in the provinces and rural areas, see him as the man who reinvigorated Turkey's self-esteem and made the country a diplomatic heavyweight.

His reaction to the country's devastating earthquake was variously praised and criticised.

His supporters say he offered leadership when pitched against a natural disaster that would have overwhelmed others; his detractors point to the numerous buildings that collapsed due to lax building controls, and to people left to die without help.

Erdogan's reaction to the devastating earthquake was praised and criticised

Erdogan's reaction to the devastating earthquake was praised and criticised

And that, perhaps, is Erdogan. A polarising figure, who, like his peers in the club of strongman leaders (Orbán, Trump, Bolsonaro to name but three) believes that you should never apologise or compromise.

Certainly Erdogan has been hard to ignore in recent months and years. He is presently blocking Sweden from joining NATO, for instance, while also trying to maintain good relations with both Russia and Ukraine.

The chances of an Erdogan-led Turkey joining the European Union, for which it has been a candidate for decades, are all but zero.

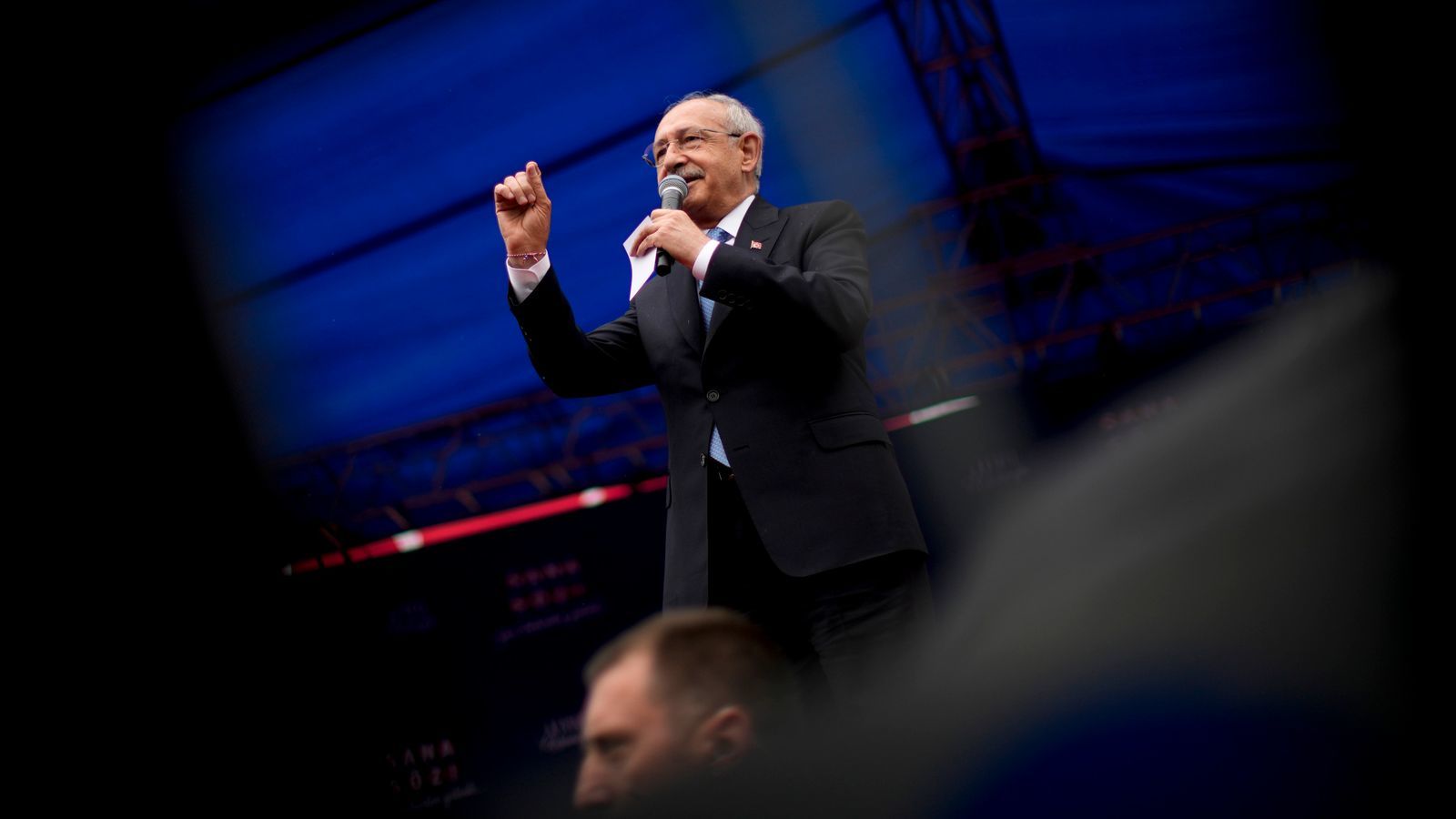

Kilicdaroglu could barely offer a greater contrast

Erdogan is an unapologetic bruiser. And yet now, set against him, is his political opposite - a politician who owes his position to being conciliatory, reserved and thoughtful.

Kemal Kilicdaroglu (right) hopes to unseat Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Kemal Kilicdaroglu (right) hopes to unseat Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Kemal Kilicdaroglu is 74 years old, a former civil servant who is now portrayed by his supporters as the key to a fresh start. He leads the Republican People's Party (CHP) but has spent the past few years slowly creating a coalition of opposition parties.

Now, he has the backing of six different parties, ranging across the political spectrum, united by the single ambition to dethrone Erdogan.

Kilicdaroglu could barely offer a greater contrast. His rhetoric is quiet, wordy, thoughtful. He talks about tolerance and religious freedom - he identifies as Alevi, a religious group that has often suffered discrimination. Erdogan has long proudly promoted his own Sunni identity.

Kilicdaroglu's ambitions are more moderate, conciliatory and, when it comes to the economy, orthodox.

Kilicdaroglu is an ex-civil servant portrayed by supporters as the key to a fresh start.

Kilicdaroglu is an ex-civil servant portrayed by supporters as the key to a fresh start.

"He's calm and quiet," says Demir Murat Seyrek, a senior policy analyst from the European Foundation for Democracy. "He comes on Twitter every evening from his kitchen to explain his policies. He's modest but maybe people need that after so much screaming in our politics.

"And young people, especially, see what life is like for other young people in Europe, and they hear about life before the AKP, and they want that - a freer life."

Election represents 'a last chance for democracy'

"It's probably one of the most significant elections in the modern history of Turkey," says Murat Seyrek. "It is seen, by some, as a last chance for democracy. They think things will get worse if the AKP is elected again."

The likelihood is that, faced with competition from other candidates who will pick up a few percentage points of support, neither Erdogan nor Kilicdaroglu will earn the outright majority required to win the election in this, the first round. In that case, the pair will engage in a second, and decisive, round of voting, on 28 May.

By then, we will know the results of the parliamentary elections, which are also being held this weekend.

Those, of course, are crucial, albeit that, during Erdogan's tenure, the power of the parliament has been eroded. But few question that it is the presidential poll that is the star attraction here.

Erdogan has been the Turkish premier since 2014.

Erdogan has been the Turkish premier since 2014.

And the ripples will spread far, whatever the outcome. Should Erdogan win another term, the expectation is that authoritarianism will take a firmer grip, that the independence of the judiciary will be challenged further and that Turkey will continue its detachment from the West.

But if Kilicdaroglu wins, then everything might just change in a whirl of political upheaval.

Kilicdaroglu's ambitions are more moderate and when it comes to the economy, orthodox.

Kilicdaroglu's ambitions are more moderate and when it comes to the economy, orthodox.

The country will, surely, ease its way back towards closer ties with Europe and, perhaps, a step away from Putin. Political prisoners should be released; religious differences tolerated; journalists allowed more freedom to report.

But this is no easy vision. Tackling the tanking economy will mean raising interest rates, probably painfully high, which will mean months, if not a couple of years, or pain for the Turkish population.

All eyes on what could be the world's most important election this year

It would be daft to think that, even under a more benevolent leader, Turkey's ambition of EU membership is going to come true any time soon.

But the relationship would be better, even if Kilicdaroglu's plans on dealing with migration, and the huge number of migrants, remain uncertain.

But Kilicdaroglu would mollify the Western world.

Sweden would be allowed to join NATO, the United States would breathe easier and foreign investment would, in the longer term, probably begin to return to Turkish businesses.

A country long seen as a chronically volatile junction between Europe, Asia and the Middle East might - just might -become a little calmer.

Turkey waits and watches, and so do many others. This may well be the most important election in the world this year.